Everyone in this family has been through Basic Training, courtesy of the U.S. Army.

That's right, do not mess with us, we're all trained killers.

Well, except, my dearest and only daughter.

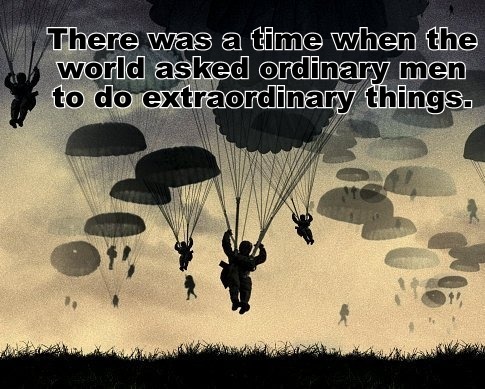

That being said, we are extremely grateful to all service members and their families who

gave so much. And I mean all of them. Throughout the history of our great country.

Hooah!

![[American soldiers landing on Omaha Beach, D-Day, Normandy, France], June 6, 1944 ©International Center of Photography/Magnum Photos](http://24.media.tumblr.com/b0f967c4ae3efc269d96ae3fc83c192f/tumblr_mnzmvqNtQ11ram6tgo2_500.jpg)

![[American soldiers landing on Omaha Beach, D-Day, Normandy, France], June 6, 1944 ©International Center of Photography/Magnum Photos](http://25.media.tumblr.com/48cbe1e0ca3463a0d0e41f6b4c24b86b/tumblr_mnzmvqNtQ11ram6tgo1_500.jpg)

![[American soldiers landing on Omaha Beach, D-Day, Normandy, France], June 6, 1944 ©International Center of Photography/Magnum Photos](http://24.media.tumblr.com/195f2d2b177498d702e82dcc44d8d294/tumblr_mnzmvqNtQ11ram6tgo3_250.jpg)

The Story Behind Robert Capa’s Pictures of D-Day

Today is the 69th anniversary of D-Day, the beginning of the massive Allied invasion of western Europe to confront Hitler’s forces during World War II. Robert Capa famously made some of the only surviving pictures of the invasion on Omaha beach, which was chaotic, in part due to wind and current. The beach rockets intended to stun the Germans arrived too early and the aerial bombs landed too far inland. Many infantrymen deemed it suicidal to attempt to cross the open beach, so the waterline was soon mobbed with crouching, pinned-down men without officers to lead them forward. Capa, who had crossed the Channel with the soldiers, remained photographing on the beach for about an hour and a half that morning until his film was used up. He then boarded a ship to take him off the beach, which subsequently was hit and sank, and then made it back on another boat, where medics were treating the wounded. He arrived back in Weymouth, England, on the morning on June 7, handed his film to the Army courier, and returned to France.

When his film arrived in the Life London office that evening, there were four rolls of 35mm film (one of them probably unexposed) and half a dozen rolls of 2 1/4 film. Capa included a note with his films saying that the action was all on the 35mm rolls. Picture editor John Morris told photographer Hans Wild and the young lab assistant, Dennis Banks, to rush the prints. When the film came out of the developing solution, Wild looked at it wet and told Morris that although the 35mm negatives were grainy, the pictures were fabulous. A few minutes later, Banks burst into Morris’s office, blurting out hysterically, “They’re ruined! Ruined! Capa’s films are all ruined!” Because of the necessary rush to get prints on the flight to New York for the next edition of Life, he had put the 35mm negatives in the drying cabinet with the heat on high and closed the door. With no air circulating, the film emulsion had melted. Although the first three rolls had nothing on the film, there were images on the fourth. The film Capa had shot with his Rollei before and after the actual landings had not been put into the drying cabinet and so survived intact.

Although ten of the 35mm negatives were usable, the emulsion on them had melted just enough so that it slid a bit over the surface of the film. Consequently, sprocket holes—which would normally punctuate the unexposed margin of the film—cut into the lower portion of the images themselves. Ironically, the blurring of the surviving images may actually have strengthened their dramatic impact, for it imbues them with an almost tangible sense of urgency and explosive reverberation.

Written by Cynthia Young, ICP Curator of the Capa Archives

No comments:

Post a Comment